|

| Hui children in traditional attire |

| Total population |

|---|

| Languages |

|

Mandarin, Dungan, other Chinese dialects and languages |

| Religion |

|

Sunni Islam |

| Related ethnic groups |

|

Han Chinese and other Sino-Tibetan ethnic groups |

The Hui Chinese people (Chinese: 回族, Xiao'erjing: حواري) are the native people of China that practice the religion of Islam. Islam is one of China's most practiced religions, and has a profound impact on the history of China.

Many of the important diplomats that have served in many of China's historical dynasties were Hui Chinese people. They have become skilled astronamers, eunuchs, travellers and soldiers.

Although the Hui people form the majority of China's Muslim population, not all of Chinese Muslims are Huis and vice versa. The Hui people are the native speakers of Sino-Tibetan languages and are closely related to the Han Chinese, and practice Islam. China is also home to non-Hui and non-Han practitioners of Islam, such as the Uyghurs, a Turkic group in the Xinjiang Region and the Dongxiang people, a Mongolic group.

The Hui Chinese people practice a distinct fushion of Chinese and Islamic culture and prepare a cuisine that rejects pork consumption (pork is one of the most consumed meats in Chinese cuisine). Hui Chinese also have spawned a distinct type of clothing and fashion.

History[]

Tang Dynasty[]

Islam was brought to China during the Tang dynasty by Arab traders, who were primarily concerned with trading and commerce, and less concerned with spreading Islam. They did not try to convert Chinese and only did commerce. It was because of this low profile that the 845 anti Buddhist edict during the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution said absolutely nothing about Islam.[1] It seems that trade occupied the attention of the early Muslim settlers rather than religious propagandism; that while they observed the tenets and practised the rites of their faith in China, they did not undertake any strenuous campaign against either Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, or the State creed, and that they constituted a floating rather than a fixed element of the population, coming and going between China and the West by the oversea or the overland routes.[2][3]

Song Dynasty[]

During the Song Dynasty, Muslims had come to play a major role in foreign trade.[4][5] The office of Director General of Shipping was consistently held by a Muslim during this period.[6] The Song Dynasty hired Muslim mercenaries form Bukhara to fight against Khitan nomads. 5,300 Muslim men from Bukhara were encouraged and invited to move to China in 1070 by the Song emperor Shenzong to help battle the Liao empire in the northeast and repopulate areas ravaged by fighting. The emperor hired these men as mercenaries in his campaign against the Liao empire. Later on these men were settled between the Sung capital of Kaifeng and Yenching (modern day Beijing). The provinces of the north and north-east were settled in 1080 when 10,000 more Muslims were invited into China.[7] They were led by the Amir of Bukhara, Sayyid "So-fei-er" in Chinese. He is called the "Father" of Chinese Islam. Islam was named by the Tang and Song Chinese as Dashi fa ("law of the Arabs").[8] He gave Islam the new name of Huihui Jiao ("the Religion of the Huihui").[9]

Yuan Dynasty[]

The Yuan Dynasty, which was ruled by Mongol emperors, deported thousands of Central Asian Muslims, Jews, and Christians into China where they formed the Semu class. Semu people like Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar, who served the Yuan dynasty in administrative positions became progenitors of many Hui people. Despite the high position given to Muslims, some policies of the Yuan Emperors severe discriminated against them, forbidding Halal slaughter and other Islamic practices like circumcision, as well as Kosher butchering for Jews, forcing them to eat food the Mongol way.[10] Toward the end, corruption and the persecution became so severe that Muslim Generals joined Han Chinese in rebelling against the Mongols. The Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang had Muslim Generals like Lan Yu who rebelled against the Mongols and defeated them in combat. Some Muslim communities had the name in Chinese which meant "baracks" and also mean "thanks", many Hui Muslims claim it is because that they played an important role in overthrowing the Mongols and it was named in thanks by the Han Chinese for assisting them.[11] The Muslims in the semu class also revolted against the Yuan dynasty in the Ispah Rebellion but the rebellion was crushed and the Muslims were massacred by the Yuan loyalist commander Chen Youding.

Ming Dynasty[]

The Ming policy towards the Islamic religion was tolerant, while their racial policy towards ethnic minorities was of integration through forced marriage. Muslims were allowed to practice Islam, but if they were members of other ethnic groups they were required by law to intermarry, so Hui had to marry Han since they were different ethnic groups, with the Han often converting to Islam.

The Ming Dynasty employed many Muslims and the Ming Emperor treated Muslims relatively freely. Some Hui people even claimed that the first Ming Emperor Ming Taizu could possibly be a Muslim, but this is rejected by the majority of scholars.[12] Hui troops were also used by the Ming Dynasty to crush the Miao and other aboriginal rebels during the Miao Rebellions, and were also settled in Changde, Hunan, where their descendants still live.[13] Muslims in Ming Dynasty Beijing were given relative freedom by the Chinese, with no restrictions placed on their religious practices or freedom of worship, and being normal citizens in Beijing. In contrast to the freedom granted to Muslims, followers of Tibetan Buddhism and Catholicism suffered from restrictions and censure in Beijing.[14]

Marriage between upper class Han Chinese and Hui Muslims was low, since upper class Han Chinese men would both refuse to marry Muslim women, and forbid their daughters from marrying Muslim men, since they did not want to convert due to their upper class status. Only low and mean status Han Chinese men would convert if they wanted to marry a Hui woman. Ming law allowed Han Chinese men and women to not have to marry Hui, and only marry each other, while Hui men and women were required to marry a spouse not of their race.[15][16][17]

The Ming Emperor Hongwu decreed the building of multiple mosques throughout China in many locations. A Nanjing mosque was built by the Xuanzong Emperor.[18]

When the Qing dynasty invaded the Ming dynasty in 1644, Hui Muslim Ming loyalists led by Muslim leaders Milayin, Ding Guodong, and Ma Shouying led a revolt in 1646 against the Qing during the Milayin rebellion in order to drive the Qing out and restore the Ming Prince of Yanchang Zhu Shichuan to the throne as the emperor. The Muslim Ming loyalists were crushed by the Qing with 100,000 of them, including Milayin and Ding Guodong killed.

Dungan revolt (1862-1877)[]

The Dungan Revolt (Chinese: 同治新疆回變 Tóngzhì Xīnjiāng Huí Biàn) was a mainly ethnic war in 19th-century China also known as the Hui Minorities War. The term is sometimes used to include the Panthay Rebellion in Yunnan, which occurred during the same period. However, this article relates specifically to the uprising by members of the Muslim Hui and other Muslim ethnic groups in China's Shaanxi, Gansu and Ningxia Provinces, as well as Xinjiang, between 1862 and 1877. The revolt arose over a pricing dispute involving bamboo poles, when a Han merchant selling to a Hui did not receive the amount demanded for the goods.

The uprising occurred on the western bank of the Yellow River in Shaanxi, Gansu and Ningxia, but excluded Xinjiang Province. It was chaotic affair and often involved diverse warring bands and military leaders with no common cause or a single specific goal. A common misconception is that the revolt was directed against the Qing dynasty, but there is no evidence to show that the rebels intended to attack the capital, Beijing, or to overthrow the entire Qing government. When the rebellion failed, mass emigration of the Dungan people from Ili into Imperial Russia ensued.

Panthay rebellion (1856-1873)[]

The Panthay Rebellion (1856–1873), known in Chinese sources as the Du Wenxiu Rebellion (Tu Wen-hsiu Rebellion; (Chinese: 杜文秀起义), was a rebellion of the Muslim Hui people and other (non-Muslim) ethnic minorities against the Manchu rulers of the Qing Dynasty in southwestern Yunnan Province, as part of a wave of Hui-led multi-ethnic unrest.

The name "Panthay" is a Burmese word, which is said to be identical with the Shan word Pang hse.[19] It was the name by which the Burmese called the Chinese Muslims who came with caravans to Burma from the Chinese province of Yunnan. The name was not used or known in Yunnan itself.[20]

The revolt was not religious in nature, since the Muslims were joined by non-Muslim Shan and Kakhyen and other hill tribes in the revolt.[21] A British officer testified that the Muslims did not rebel for religious reasons, and that the Chinese were tolerant of different religions and were unlikely to have caused the revolt by interfering with the practicing of Islam.[22] In addition, loyalist Muslim forces helped Qing crush the rebel Muslims.[23]

The war was not also aimed at Han, but rather ruling Manchus. Du Wenxiu (Chinese: 杜文秀), the main leader of the rebellion also mandated the use of Arabic language in the regime and banned pork consumption. Ma Rulong (Chinese: 馬如龍) was another prominent rebel leader, but he surrendered to the Qinq forces and joined them.

It is also during this rebellion that the glaring differences between followers of certain Islamic sections began to fire back.

Second Dungan revolt (1895–1896)[]

The Dungan Revolt (1895) was a rebellion of various Muslim ethnic groups in Qinghai and Gansu against the Qing Dynasty, that originated because of a violent dispute between two Sufi orders of the same sect. The Wahhabi inspired Yihewani organization then joined in and encouraged the revolt, which was crushed by loyalist Muslims.

Within the Republic of China[]

During the Second Sino-Japanese war the Japanese followed what has been referred to as a "killing policy" and destroyed many mosques. According to Wan Lei, "Statistics showed that the Japanese destroyed 220 mosques and killed countless Hui people by April 1941." After the Rape of Nanking mosques in Nanjing were found to be filled with dead bodies.They also followed a policy of economic oppression which involved the destruction of mosques and Hui communities and made many Hui jobless and homeless. Another policy was one of deliberate humilation. This included soldiers smearing mosques with pork fat, forcing Hui to butcher pigs to feed the soldiers, and forcing girls to supposedly train as geishas and singers but in fact made them serve as sex slaves. Hui cemeteries were destroyed for military reasons.[24] Many Hui fought in the war against Japan.

Language[]

The Hui people are speakers of Sino-Tibetan languages. They are fluent in Mandarin, which is an official language in China and the lingua franca of all of China's ethnic groups. They also speak other various Chinese dialects that are truly no different than those spoken by the Hans. The Hui of Yunnan (Burmese called them Panthays) were reported to be fluent in Arabic.[25] During the Panthay Rebellion, Arabic replaced Chinese as official language of the rebel kingdom.[26] In Tianmu (Chinese: 天穆村), Tianjin, Hui could speak an old, archaic form of Arabic, when they met Arab Muslims in recent times, it was found out that Old Arabic and Modern Arabic were very different, so Modern Arabic is now being taught to Hui.[27][28]

In 1844 "The Chinese repository, Volume 13" was published, including an account of an Englishman who stayed in the Chinese city of Ningbo. There he visited the local mosque, the Hui running the mosque was from Shandong, and he was a descendant of Muslims from the Arabian city of Medina. He was able to read and speak Arabic with ease, but was totally illiterate in Chinese. He was born in China and spoke Chinese as well.[29]

Writing System[]

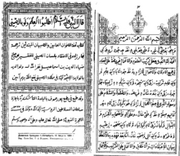

An Arabic book on Islamic ritual, with a parallel Chinese translation in the Xiao'erjing script, published in Tashkent in 1899

The Hui Chinese write most of the their languages in the Hanza script, the system of writing used for most languages in China. However, like most civilizations that adopted Islam, a version of the Arabic script (known as Perso-Arabic) was used for the native languages. In China's case, the use of Perso-Arabic to write Chinese and Sino-Tibetan languages was known as Xiao'erjing (Chinese: 本經). It is used primarily by spakers of the Dungan language. The speakrs from Central Asia use the Cyrillic script, due to the historical Russian and later Soviet occupation of Central Asia.

Religion[]

Although Islam is the religion of the Hui people, they are divided by practitioners of different sections. Because of China's complex history, many Muslims in China practice a mix of Islam and Chinese folk religion as well as elements of Buddhism, Confucianism and other spiritual religious in China.

Gedimu []

Most Huis follow the Hanafi section of Islam, a branch within the Sunni (traditional) section of Islam. They are known as Gedimu (Chinese: 格迪目) in China or Qadim (Arabic: قديم). This is the earliest school of Islam that was introduced in China.

People who belong to Gedimu follow a form of Islamic education known as Jingtang Jiaoyu (Chinese: 经堂教育), which is very influenced by Han Chinese culture and follows many elements of mainstream Chinese culture. Because of its pride and conservativeness in Chinese culture, adherants are criticized for their wrong pronounciations of Arabic.

Yihewani[]

Yihewani (Chinese: 伊赫瓦尼), or Ikhwan (Arabic: الإخوان),(also known as Al Ikhwan al Muslimun, which means Muslim Brotherhood, but not to be confused with the Middle Eastern Muslim Brotherhood) is an Islamic sect in China. Its adherents are called Sunnaiti. It is also Hanafi,[30] non-Sufi school of the Sunni tradition. It is also referred to as "new sect" “[31] or "Latest sect".[32]

It is mainly in Qinghai, Ningxia and Gansu (there in Linxia) and distributed in Beijing, Shanghai, Henan, Shandong and Hebei.[33] It was the end of the 19th century when the Dongxiang imam Ma Wanfu (1849–1934) from the village of Guoyuan in Hezhou (now the Dongxiang Autonomous County was founded in Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture, Gansu Province) - who had studied in Mecca and was influenced by the Wahabi movement. After his return to Gansu and he founded the movement with the so-called ten major Ahong.[34] The school rejected the Sufism. It claimed that the rites and ceremonies not standing in line with the Quran and the Hadith should be abolished. It is against grave and Murschid (leader / teacher) worship, and advocates against preaching and da'wa done in Chinese.[35] In 1937 It divided into two groups.[36]

Jahriyya[]

Jahriyya (also spelled Jahrīya or Jahriyah) is a Sufi order in China. Founded in the 1760s by Ma Mingxin, it has been active in the late 18th and 19th centuries in the then Gansu Province (also including today's Qinghai and Ningxia), when its followers participated in a number of conflicts with other Muslim groups and in several rebellions against the China's ruling Qing Dynasty.

The name comes from the Arabic word jahr (Arabic: جهر), referring to their practise of vocal performance of the dhikr. This contrasted with the more typical Naqshbandi practise, observed by the Khufiyya, of performing it silently.[37]

Art[]

The Hui Chinese people practice an artistic culture that contains a blend and fushion of Chinese and Islamic art.

Dress and Fashion[]

Hui Chinese performing a folk song, in traditional Hui dress

The Hui Chinese dress according to Islamic tradition. The men usually where a cap known as a taqiyah (Arabic: طاقية), which a headdress worn commonly in Muslim nations. The women usually where the traditional headscarf known as the hijab (Arabic: حجاب), another headdress typically worn by women in Muslim nations.

Distinct Chinese-Islamic Practices[]

The Hui Chinese also practiced a form of religious culture that was not typical in other Muslim countries. However, they also do practice orthodox Islamic tradition such as - rejecting pork consumption and alcoholic and hallucigenic consumables.

During the era of the Qing Dynasty, Muslim laws were often not followed as noted by Viscount D'Ollone, a French Commandant in China - other than banning pork consumption.

Buddhist and Confucian traditions influence the culture of the Hui Chinese. For example, the lighting of incense during worshipping time. Also, Chinese mosques were built like Buddhist temples and often did not contain a minaret.[38]

Hui Chinese also make ancestrial tablets, as do Han Chinese.

Literature[]

The Han Kitab (Chinese: 漢克塔布, Arabic: هان کتاب) was a collection of Islamic and Confucian texts written by various Hui Authors in the 18th century, including Liu Zhi.

New works were written by Hui intellectuals following education reform by Ma Clique Warlords and Bai Chongxi. Texts were also translated from Arabic.[39]

A new edition of a book by Ma Te-hsin, called Ho-yin Ma Fu-ch'u hsien-sheng i-shu Ta hua tsung kuei Ssu tien yaohui, which was printed in 1865 was reprinted in 1927 by Ma Fuxiang.[40]

The General Ma Fuxiang invested in new editions of Confucian and Islamic texts.[41] He edited Shuofang Daozhi.[42][43][44][45] a gazette, and books such as Meng Cang ZhuangKuang: Hui Bu Xinjiang fu.[46][47]

Architecture[]

Great Mosque of Xian

The architecture of the Hui Chinese in many parts of China do not emulate traditional Islamic mosques. Mosques in China are known as qīngzhēn sì (Chinese: 清真寺) which literally means "pure path temple". For the most part, mosques in China are built Buddhist-style, and resemble Buddhist temples. One distinct part of these Chinese-style mosques are the roofs, which contain an overhanging eave before an upward-slope. This tradition came from Buddhist influence. According to Chinese tradition from the Han Dynasty, this particular design was meant to ward-off evil spirits.

Mosques in western China incorporate more of the elements seen in mosques in other parts of the world. Western Chinese mosques were more likely to incorporate minarets and domes while eastern Chinese mosques were more likely to look like pagodas.[48]

An important feature in Chinese architecture is its emphasis on symmetry, which connotes a sense of

Puhaddin Mausoleum complex in Yangzhou

grandeur; this applies to everything from palaces to mosques. One notable exception is in the design of gardens, which tends to be as asymmetrical as possible. Like Chinese scroll paintings, the principle underlying the garden's composition is to create enduring flow; to let the patron wander and enjoy the garden without prescription, as in nature herself.

On the foothills of Mount Lingshan are the tombs of two of the four companions that Muhammad sent eastwards to preach Islam. Known as the "Holy Tombs," they house the companions Sa-Ke-Zu and Wu-Ko-Shun—their Chinese names, of course. The other two companions went to Guangzhou and Yangzhou.[49]

The Huaisheng Mosque is one of the oldest mosques in the world, whose construction is attributed to Prophet Muhammad's maternal uncle, Sa`d ibn Abi Waqqas.

Chinese buildings may be built with bricks, but wooden structures are the most common; these are more capable of withstanding earthquakes, but are vulnerable to fire. The roof of a typical Chinese building is curved; there are strict classifications of gable types, comparable with the classical orders of European columns.

As in all regions the Chinese Islamic architecture reflects the local architecture in its style. China is renowned for its beautiful mosques, which resemble temples. However, in western China the mosques resemble those of the middle east, with tall, slender minarets, curvy arches and dome shaped roofs. In northwest China where the Chinese Hui have built their mosques, there is a combination of east and west. The mosques have flared Chinese-style roofs set in walled courtyards entered through archways with miniature domes and minarets.[48] The first mosque was the Great Mosque of Xian, or the Xian Mosque, which was created in the Tang Dynasty in the 7th century.[50]

Cuisine[]

Niang pi (酿皮), a popular noodle-and-tofu cold dish in Linxia

Halal food has a long history in China. The term Halal (Arabic: الحلال) refers to foods that are considered permitted to consume in Islam. The arrival of Arab and Persian merchants during the Tang and Song dynasties seen the introduction of the Muslim diet. Chinese Muslim cuisine adheres strictly to the Islamic dietary rules with mutton and lamb being the predominant ingredient. The advantage of Muslim cuisine in China is that it has inherited the diverse cooking methods of Chinese cuisine for example, braising, roasting, steaming, stewing and many more. Due to China's multicultural background Muslim cuisine retains its own style and characteristics according to regions.[51] Due to the large Muslim population in western China, many Chinese restaurants cater to Muslims or cater to

Lanzhou-style Beef Lamian

the general public but are run by Muslims. In most major cities in China, there are small Islamic restaurants or food stalls typically run by migrants from Western China (e.g., Uyghurs), which offer inexpensive noodle soup. Lamb and mutton dishes are more commonly available than in other Chinese restaurants, due to the greater prevalence of these meats in the cuisine of western Chinese regions. Commercially prepared food can be certified Halal by approved agencies.

[52] In Chinese, halal is called qīngzhēn cài (Chinese: 清真菜) or "pure truth food."

Beef and lamb slaughtered according to Islamic rituals is also commonly available in public markets, especially in North China. Such

A Halal Bakery in Tuanjie St, the main street of Linxia City

meat is sold by Muslim butchers, who operate independent stalls next to non-Muslim butchers.

Northern Chinese Islamic cuisine originated in China proper with Middle Eastern flavors and dietary standards. It is heavily influenced by Beijing cuisine, with nearly all cooking methods identical, and differs only in material due to religious restrictions. As a result, northern Islamic cuisine is often included in home Beijing cuisine, however seldom in east coast restaurants. During the Yuan dynasty, Halal methods of slaughtering animals and preparing food was banned and forbidden by the Mongol emperors, starting with Genghis Khan who banned Muslims and Jews from slaughtering their animals their own way, and making them follow the Mongol method.

Notable Hui Chinese[]

| Zheng He 鄭和 |

A court eunuch, mariner, explorer, diplomat, and fleet admiral during China's early Ming Dynasty. Zheng commanded expeditionary voyages to Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and East Africa from 1405 to 1433. As a favorite of the Yongle Emperor, whose usurpation he assisted, he rose to the top of the imperial hierarchy and served as commander of the southern capital Nanjing. He is considered one of the world's greatest historical Muslim travelers. |

| Ma Fuxiang 馬福祥 |

A Chinese military and political leader spanning the Qing Dynasty through the early Republic of China and illustrated the power of family, the role of religious affiliations, and the interaction of Inner Asian China and the national government of China. Having turned to Chiang Kai-shek in 1928, he was made chairman (governor) of the government of Anhui in 1930. He was elected a member of the National Government Commission, and then appointed the mayor of Qingdao, special municipality. |

| Bai Chongxi 白崇禧 |

A Chinese general in the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China (ROC) and a prominent Chinese Nationalist Muslim leader. From the mid-1920s to 1949, Bai and his close ally Li Zongren ruled Guangxi province as regional warlords with their own troops and considerable political autonomy. His relationship with Chiang Kai-shek was at various times rivalrous and cooperative. He supported Chiang in the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War. He was the Minister of National Defense of the Republic of China from 1946 to 1948. |

| Hu Songshan 賽爾敦丁 |

An important Imam, scripturalist, and leader of the Yihewani Muslim sect in China, and a former Wahabi and Sufi. He was influential and played an important role in Chinese Islam in this position as he propagated reformist doctrines in Ningxia in his later life. Hu also played a role in rallying Muslims against the Japanese invasion of China. |

| Liu Hui 刘慧 |

A politician of the People's Republic of China and the Chairwoman (Governor) of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. A Hui native of Tianjin, she joined the Communist Party of China in December 1985. She is one of the few women among China's high-ranking officials, and has been an alternate member of the 17th and the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. |

| Liu Shishi 劉師什 |

A Chinese actress and ballerina. She is currently contracted with Chinese Entertainment Shanghai Limited. In May 2012, she was nominated for, and won the "Magnolia Award" for the most popular actress for her role in Chinese time-travel drama Scarlet Heart. |

| Zhang Linpeng 张琳芃 |

A Chinese footballer who currently plays for Guangzhou Evergrande in the Chinese Super League. He is known by the nickname Zhangmos in China for his similarity in looks and playing style as Sergio Ramos. An offensive minded defender, Zhang is also known for his tackling ability and aerial game. He was highly praised by Italian manager Marcello Lippi who described him as "the best Chinese footballer in the Chinese Super League". |

| Zhang Hongtu 張宏圖 |

A Chinese artist based in New York. He works in a variety of media such as painting (sometimes with soy sauce), sculpture, collage, ceramics, digital imaging and installation. His work explores the freedom to criticize the Chinese authorities afforded to an artist living in the West. He was born in Pingliang to a Muslim family. |

See Also[]

Sources[]

- ↑ Herbert Allen Giles (1926). Confucianism and its rivals. Forgotten Books. p. 139. ISBN 1-60680-248-8. http://books.google.com/?id=drPQaUGOJQIC. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

- ↑ Frank Brinkley (1902). China: its history, arts and literature, Volume 2. Volumes 9-12 of Trübner's oriental series. BOSTON AND TOKYO: J.B.Millet company. pp. 149, 150, 151, 152. http://books.google.com/books?id=XJqCAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA150&dq=According+to+Giles,+the+true+stock+of+the+present+Chinese+Mohammedans+was+a+small+army+of+four+thousand+Arabian+soldiers,+who,+being+sent+by+the+Khaleef+Abu+Giafar+in+755+to+aid+in+putting+down+a+rebellion,+were+subsequently+permitted#v=onepage&q=According%20to%20Giles%2C%20the%20true%20stock%20of%20the%20present%20Chinese%20Mohammedans%20was%20a%20small%20army%20of%20four%20thousand%20Arabian%20soldiers%2C%20who%2C%20being%20sent%20by%20the%20Khaleef%20Abu%20Giafar%20in%20755%20to%20aid%20in%20putting%20down%20a%20rebellion%2C%20were%20subsequently%20permitted&f=false. Retrieved 2011-12-14.Original from the University of California

- ↑ Frank Brinkley (1904). Japan [and China: China; its history, arts and literature]. Volume 10 of Japan [and China]: Its History, Arts and Literature. LONDON 34 HENRIETTA STREET, W. C. AND EDINBURGH: Jack. pp. 149, 150, 151, 152. http://books.google.com/books?id=5ukVAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA150&dq=According+to+Giles,+the+true+stock+of+the+present+Chinese+Mohammedans+was+a+small+army+of+four+thousand+Arabian+soldiers,+who,+being+sent+by+the+Khaleef+Abu+Giafar+in+755+to+aid+in+putting+down+a+rebellion,+were+subsequently+permitted#v=onepage&q=According%20to%20Giles%2C%20the%20true%20stock%20of%20the%20present%20Chinese%20Mohammedans%20was%20a%20small%20army%20of%20four%20thousand%20Arabian%20soldiers%2C%20who%2C%20being%20sent%20by%20the%20Khaleef%20Abu%20Giafar%20in%20755%20to%20aid%20in%20putting%20down%20a%20rebellion%2C%20were%20subsequently%20permitted&f=false. Retrieved 2011-12-14.Original from Princeton University

- ↑ BBC 2002, Origins

- ↑ Jonathan Neaman Lipman (2004). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 79. ISBN 0-295-97644-6. http://books.google.com/?id=Y8Nzux7z6KAC. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Ting 1958, p. 346

- ↑ ( )Raphael Israeli (2002). Islam in China: religion, ethnicity, culture, and politics. Lexington Books. p. 283. ISBN 0-7391-0375-X. http://books.google.com/?id=KoiD_yafPT8C. Retrieved December 20, 2011. "During the Sung (Song) period (Northern Sung, 960-1127, Southern Sung, 1127-1279) we again hear in the Chinese annals of Muslim mercenaries. In 1070, the Song emperor, Shen-tsung (Shenzong), invited a group of 5,300 young Arabs, under the leadership of Amir Sayyid So-fei-er (this name being mentioned in the Chinese source) of Bukhara, to settle in China. This group had helped the emperor in his war with the newly established Liao Empire (Khitan) in northeastern China. Shen-zong gave the prince an honrary title, and his men were encouraged to settle in the war-devasted (sic) areas in northeastern China between Kaifeng, the capital of the Sung, and Yenching (Yanjing) (today's Peking or Beijing) in order to create a buffer zone between the weaker Chinese and the aggressive Liao. In 1080, another group of more than 10,000 Arab men and women on horseback are said to have arrived in China to join So-fei-er. These people settled in all the provinces of the north and northeast, mainly in Shan-tung (Shandong), Ho-nan (Hunan), An-hui (Anhui), Hu-pei (Hubei), Shan-hsi (Shanxi), and Shen-hsi (Shaanxi). . .So-fei-er was not only the leader of the Muslims in his province, but he acquired the reputation also of being the founder and "father" of the Muslim community in China. Sayyid So-fei-er discovered that Arabia and Islam were"

- ↑ Israeli 2002, p. 283; Tashi or Dashi is the Chinese rendering of Tazi-the name the Persians used for the Arabs

- ↑ ( )Raphael Israeli (2002). Islam in China: religion, ethnicity, culture, and politics. Lexington Books. p. 284. ISBN 0-7391-0375-X. http://books.google.com/?id=KoiD_yafPT8C. Retrieved December 20, 2011. "misnamed by the Tang and Song Chinese as Ta-shi kuo (Dashi guo) ("the land of the Arabs") or as Ta-shi fa (Dashi fa) ("the religion, or law, of Islam"). This was derived from the ancient Chinese name for Arabia, Ta-shi (Dashi), which remained unchanged even after the great developments in Islamic history since that time. He then introduced Hui Hui Jiao (the Religion of Double Return, which meant to submit and return to Allah), to substitute for Dashi fa, and then replaed Dashi Guo with Hui Hui Guo (the Islamic state). This in Chinese Hui Hui Jiao was universally accepted and adopted for Islam by the Chinese, Khiran, Mongols, and Turks of the Chinese border lands before the end of the eleventh century."

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedDonald Daniel Leslie 1998 12 - ↑ Dru C. Gladney (1991). Muslim Chinese: ethnic nationalism in the People's Republic (2, illustrated, reprint ed.). Council on East Asian Studies, data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIABAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAEALAAAAAABAAEAQAICTAEAOw%3D%3DHarvard University. p. 234. ISBN 0-674-59495-9. http://books.google.com/?id=kkJwAAAAMAAJ&dq=Thus%2C+Changying+means+either+%22many+thanks%22+to+the+Hui+who+helped+drive+out+the+Mongols%2C+or+the+%22many+barracks%22+of+the+Hui+militia+eventually+established+there.+This+reflects+the+popular+belief+among+the+Hui+that+they+played+an+important&q=popular+belief+mongols. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Michael Dillon (1999). China's Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects. Richmond: Curzon Press. p. 29. ISBN 0-7007-1026-4.

- ↑ Chih-yu Shih, Zhiyu Shi (2002). Negotiating ethnicity in China: citizenship as a response to the state. Psychology Press. p. 133. ISBN 0-415-28372-8. http://books.google.com/?id=0rhxU662vQsC. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Susan Naquin (2000). Peking: temples and city life, 1400-1900. University of California Press. p. 214. ISBN 0-520-21991-0. http://books.google.com/?id=bANasl7nayUC. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ ()Maria Jaschok; Maria Jaschok; Jingjun Shui (2000). The history of women's mosques in Chinese Islam: a mosque of their own (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-7007-1302-6. http://books.google.com/?id=jV9_YvgUmpsC. Retrieved December 20, 2011. "Psychology Press"

- ↑ ()Jiang Yonglin; Yonglin Jiang (2011-01-12). The Mandate of Heaven and the Great Ming Code. Volume 21 of Asian law series. University of Washington Press. p. 241. ISBN 0-295-99065-1. http://books.google.com/?id=w68uObIhx9MC. Retrieved December 20, 2011. "loose-rein (jimi) policy, 104, 124 Lord of Resplendent Heaven, 106 Lord on High, 3, 25, 82, 93, 94 loyalty, ... Donald, 36, 39, 54 Muslims, Qincha Hui, 124, 128, 131 "mutual production and mutual destruction," 79 Nanjing, 22--23,"

- ↑ ()Gek Nai Cheng (1997). Osman Bakar. ed. Islam and Confucianism: a civilizational dialogue. Published and distributed for the Centre for Civilizational Dialogue of University of Malaya by University of Malaya Press. p. 77. ISBN 983-100-038-2. http://books.google.com/?id=UyHYAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved December 20, 2011.

- ↑ ()Maria Jaschok; Maria Jaschok; Jingjun Shui (2000). The history of women's mosques in Chinese Islam: a mosque of their own (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-7007-1302-6. http://books.google.com/?id=jV9_YvgUmpsC. Retrieved December 20, 2011. "For instance, in the early years of Emperor Hongwu's reign in the Ming Dynasty ' His Majesty ordered to have mosques built in Xijing and Nanjing [the capital cities], and in southern Yunnan, Fujian and Guangdong. His Majesty also personally wrote baizizan [a eulogy] in praise of the Prophet's virtues'. The Ming Emperor Xuanzong once issued imperial orders to build a mosque in Nanjing in response to Zheng He's request (Liu Zhi, 1984 reprint: 358-374). Mosques built by imperial decree raised the social position of Islam, and assistance from upper-class Muslims helped to sustain religious sites in certain areas."

- ↑ Scott 1900, p. 607

- ↑ Yule & Burnell 1968, p. 669

- ↑ Fytche 1878, p. 300

- ↑ Fytche 1878, p. 301

- ↑ Joseph Mitsuo Kitagawa (2002). The religious traditions of Asia: religion, history, and culture. Routledge. p. 375. ISBN 0-7007-1762-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=5LSvkQvvmAMC&pg=PA283&dq=arab+mercenaries+china&q=arab+mercenaries+china&hl=en#v=onepage&q=yunnan%20rebellion%20loyalist&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ LEI, Wan ((2010/2)). "The Chinese Islamic “Goodwill Mission to the Middle East” During the Anti-Japanese War". DÎVÂN DİSİPLİNLERARASI ÇALIŞMALAR DERGİSİ cilt 15 (sayı 29): 139-141. http://www.academia.edu/4427135/The_Chinese_Islamic_Goodwill_Mission_to_the_Middle_East_-_Japonyaya_Karsi_Savasta_Cinli_Muslumanlarin_Orta_Dogu_iyi_Niyet_Heyeti_-_Wan_LEI. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ↑ Albert Fytche (1878). Burma past and present. C. K. Paul & co.. p. 301. http://books.google.com/books?id=K28oAAAAYAAJ&q=arabic#v=snippet&q=many%20of%20them%20are%20able%20to%20converse%20arabic&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Journal of Southeast Asian studies, Volume 16. McGraw-Hill Far Eastern Publishers. 1985. p. 117. http://books.google.com/?id=3MJBAAAAYAAJ&q=Although+he+and+his+court+adopted+traditional+Chinese+dress,+he+decreed+that+his+subjects+should+use+the+Arabic+language+and+honour+Muslim&dq=Although+he+and+his+court+adopted+traditional+Chinese+dress,+he+decreed+that+his+subjects+should+use+the+Arabic+language+and+honour+Muslim. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Michael Dillon (1999). China's Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects. Richmond: Curzon Press. p. 155. ISBN 0-7007-1026-4. http://books.google.com/?id=hUEswLE4SWUC. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ 天穆村掀起学习阿拉伯语热潮

- ↑ The Chinese repository, Volume 13. Printed for the proprietors. 1844. p. 31. http://books.google.com.au/books?id=6wEMAAAAYAAJ&q=mohammedan#v=onepage&q=mohammedan%20temple%20arabic&f=false. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ↑ One of the four major schools of Islam.

- ↑ chinese Xinjiao pai 新教派

- ↑ chin. Xinxinjiao 新新教

- ↑ Cihai, S. 2002.

- ↑ chin. shi da ahong 十大阿訇; das Cihai spricht von zehn großen Hadschis (shi da haji 十大哈吉).

- ↑ Shoujiang Mi, Jia You (Kap.2.2.: "Birth and Growth of Sects and Menhuans")

- ↑ chinaculture.org: Yihewani pai (found on March 27, 2010)

- ↑ Gladney 1996, pp. 48–49

- ↑ Michael Dillon (1999). China's Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects. Richmond: Curzon Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-7007-1026-4. http://books.google.com/?id=hUEswLE4SWUC. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Masumi, Matsumoto. "The completion of the idea of dual loyalty towards China and Islam". http://science-islam.net/article.php3?id_article=676&lang=fr. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Mary Clabaugh Wright (1957). Last Stand of Chinese Conservatism the T'Ung-Chih. Stanford University Press. p. 406. ISBN 0-8047-0475-9. http://books.google.com/?id=VaOaAAAAIAAJ. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Jonathan Neaman Lipman (2004). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-295-97644-0. http://books.google.com/?id=90CN0vtxdY0C&pg=PA169&dq=ma+fulu+and+four+cousins#v=onepage&q=ma%20fuxiang%20titular%20director%20islamic%20school&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Shuo fang dao zhi. 1926. http://books.google.com/?id=PCktSQAACAAJ&dq=shuofang+daozhi.

- ↑ Ma Fuxiang (1926). Shuo fang dao zhi. http://books.google.com/?id=5ybyHgAACAAJ&dq=shuofang+daozhi.

- ↑ Shuo fang dao zhi. 1926. http://books.google.com/?id=PCktSQAACAAJ&dq=shuofang+daozhi.

- ↑ 马福祥(Ma Fuxiang) (1987). Shuo fang dao zhi 31st Edition(朔方道志: 31卷). Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House(天津古籍出版社). http://books.google.com/?id=5ybyHgAACAAJ&dq=shuofang+daozhi.

- ↑ 馬福祥(Ma Fuxiang) (1931). 蒙藏狀况: 回部新疆坿 (Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Status: Mikurube Xinjiang Agricultural Experiment Station). Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission(蒙藏委員會). http://books.google.com/?id=tVq1GwAACAAJ&dq=%E8%92%99%E8%97%8F%E7%8B%80%E5%86%B5:+%E5%9B%9E%E9%83%A8%E6%96%B0%E7%96%86%E5%9D%BF.

- ↑ inauthor:"马福祥" - Google Search

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Cowen, Jill S. (July–August 1985), "Muslims in China: The Mosque", Saudi Aramco World: 30–35, http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/198504/muslims.in.china-the.mosques.htm, retrieved 2006-04-08

- ↑ The Muslim History of China

- ↑ China By Shelley Jiang,pg. 274

- ↑ Halal Food in China from Muslim2China

- ↑ Halal Food