No edit summary |

FilipinoMan (talk | contribs) (Undo revision 12712 by 2602:306:3394:3020:6554:2CDC:6928:3AEF (talk)) |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

Yemenite Jews have a unique religious tradition that marks them out as separate from Ashkenazi, Sephardi and other [[Jews|Jewish]] groups. It is debatable whether they should be described as "[[Mizrahi Jews]]", as most other Mizrahi groups have over the last few centuries undergone a process of total or partial assimilation to Sephardic culture and liturgy. (While the Shami sub-group of Yemenite Jews did adopt a Sephardic-influenced rite, this was for theological reasons and did not reflect a demographic or cultural shift). |

Yemenite Jews have a unique religious tradition that marks them out as separate from Ashkenazi, Sephardi and other [[Jews|Jewish]] groups. It is debatable whether they should be described as "[[Mizrahi Jews]]", as most other Mizrahi groups have over the last few centuries undergone a process of total or partial assimilation to Sephardic culture and liturgy. (While the Shami sub-group of Yemenite Jews did adopt a Sephardic-influenced rite, this was for theological reasons and did not reflect a demographic or cultural shift). |

||

| − | Although |

+ | Although arguably native to Yemen, the ancient Yemenite Jews are normally accepted as being [[Arabs|Arab]] or "Arab Jews" ({{Arabic|اليهود العرب}}, {{Lang-he-n|יהודים ערבים}}) and understood to be natives of South Arabia that converted to Judaism. But most Jews today of Yemenite descent do not consider themselves [[Arabs|Arab]] (albeit they do not speak Arabic mostly) But they are in fact the descendants of ancient Israelite migrants that settled in Yemen. |

==History== |

==History== |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

Traces of the existance of Judaism in South Arabia (now Yemen) were mostly during the formation of ancient Yemenite kingdoms. Among those, Paganism was also predominant. These ancient Arabian states became subject to invasion attempts from the Romans. Aelius Gallus, the Roman governer of occupied-Egypt had tried to conquer the city of Najran but failed to. The Romans later referred to southern Arabia as "''Arabia Felix''" which means "Happy Arabia" in Old Latin. Among the predominant kingdoms were Himyar, Saba and Qataban. Byzantium emperor Justinian I sent a fleet to Yemen and Joseph Dhu Nuwas was killed in battle in 525 CE <ref>J. A. S. Evans.The Age of Justinian: The Circumstances of Imperial Power p.113</ref> western coasts of Yemen became a puppet state until a Himyarite nobility managed to dr[[File:Griffin.jpg|thumb|<small>An ancient griffin found in Yemen</small>]]ive out the occupiers completely and those nobles were [[Jews]] as well <ref>The Jews of Yemen: Studies in Their History and Culture By Joseph Tobi p.34</ref> |

Traces of the existance of Judaism in South Arabia (now Yemen) were mostly during the formation of ancient Yemenite kingdoms. Among those, Paganism was also predominant. These ancient Arabian states became subject to invasion attempts from the Romans. Aelius Gallus, the Roman governer of occupied-Egypt had tried to conquer the city of Najran but failed to. The Romans later referred to southern Arabia as "''Arabia Felix''" which means "Happy Arabia" in Old Latin. Among the predominant kingdoms were Himyar, Saba and Qataban. Byzantium emperor Justinian I sent a fleet to Yemen and Joseph Dhu Nuwas was killed in battle in 525 CE <ref>J. A. S. Evans.The Age of Justinian: The Circumstances of Imperial Power p.113</ref> western coasts of Yemen became a puppet state until a Himyarite nobility managed to dr[[File:Griffin.jpg|thumb|<small>An ancient griffin found in Yemen</small>]]ive out the occupiers completely and those nobles were [[Jews]] as well <ref>The Jews of Yemen: Studies in Their History and Culture By Joseph Tobi p.34</ref> |

||

===='''Himyarite Kingdom 110-525 A.D.'''==== |

===='''Himyarite Kingdom 110-525 A.D.'''==== |

||

| − | Yarab, a descendant of the Biblical patriarchs Noah, Shem and Joktan and considered a founding father of an [[File:300px-Map_of_Aksum_and_South_Arabia_ca_230_AD.jpg|thumb|245px|<small>Map of the South Arabian kingdoms and the African kingdom of Aksum</small>]]early spoken Arabic and culture (by Muslims) united Yemen and his descendants created the civilization known as the Himyarites ({{Arabic|الحميريون}} ''Banu Himyar''), or the Kingdom of Himyar who became a dominant polity in South Arabia.<ref>http://fanack.com/countries/yemen/history/the-himyarite-kingdom</ref> The Himyarites' capital was based in the city of Zafar and then to the modern-day city of Sana'a.<ref>http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/5159-dhu-nuwas-zur-ah-yusuf-ibn-tuban-as-ad-abi-karib</ref> The Himyarite kingdom is also significant to the history of Judaism, as many of its kings and leaders were known to be sadistic converts to Judaism. |

+ | Yarab, a descendant of the Biblical patriarchs Noah, Shem and Joktan and considered a founding father of an [[File:300px-Map_of_Aksum_and_South_Arabia_ca_230_AD.jpg|thumb|245px|<small>Map of the South Arabian kingdoms and the African kingdom of Aksum</small>]]early spoken Arabic and culture (by Muslims) united Yemen and his descendants created the civilization known as the Himyarites ({{Arabic|الحميريون}} ''Banu Himyar''), or the Kingdom of Himyar who became a dominant polity in South Arabia.<ref>http://fanack.com/countries/yemen/history/the-himyarite-kingdom</ref> The Himyarites' capital was based in the city of Zafar and then to the modern-day city of Sana'a.<ref>http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/5159-dhu-nuwas-zur-ah-yusuf-ibn-tuban-as-ad-abi-karib</ref> The Himyarite kingdom is also significant to the history of Judaism, as many of its kings and leaders were known to be sadistic converts to Judaism. |

===='''Kingdom of Saba/Sheba '''==== |

===='''Kingdom of Saba/Sheba '''==== |

||

Revision as of 08:01, 25 October 2017

The Yemenite Jews (Hebrew: יהודי תימן Yehudim tēmānim, Arabic: اليهود اليمنيين al-Yahud al-yamaniyyah) are those Jews who live, or whose recent ancestors lived, in Yemen. Between June 1949 and September 1950, the overwhelming majority of Yemen's Jewish population was transported to Israel in Operation Magic Carpet. Most Yemenite Jews now live in Israel, with some others in the United States, and fewer elsewhere. Only a handful remain in Yemen, mostly elderly.

Yemenite Jews have a unique religious tradition that marks them out as separate from Ashkenazi, Sephardi and other Jewish groups. It is debatable whether they should be described as "Mizrahi Jews", as most other Mizrahi groups have over the last few centuries undergone a process of total or partial assimilation to Sephardic culture and liturgy. (While the Shami sub-group of Yemenite Jews did adopt a Sephardic-influenced rite, this was for theological reasons and did not reflect a demographic or cultural shift).

Although arguably native to Yemen, the ancient Yemenite Jews are normally accepted as being Arab or "Arab Jews" (Arabic: اليهود العرب, Hebrew: יהודים ערבים) and understood to be natives of South Arabia that converted to Judaism. But most Jews today of Yemenite descent do not consider themselves Arab (albeit they do not speak Arabic mostly) But they are in fact the descendants of ancient Israelite migrants that settled in Yemen.

History

Early History and Ancestry

There are numerous accounts and legends concerning the arrival of Jews in various regions in Southern Arabia. One legend suggests that King Solomon sent Jewish merchant marines to Yemen to prospect for gold and silver with which to adorn the Temple in Jerusalem [1] In 1881, the French vice consulate in Yemen wrote to the leaders of the Alliance in France, that he read a book by the Arab historian Abu-Alfada, which stated that the Jews of Yemen settled in the area in 1451 BCE [2] Another legend says that Yemeni tribes converted to Judaism after the Queen of Sheba's visit to king Solomon [3] The Sanaite Jews have a legend that their ancestors settled in Yemen forty-two years before the destruction of the First Temple. It is said that under the prophet Jeremiah some 75,000 Jews, including priests and Levites, traveled to Yemen.[4] Another legend states that when Ezra commanded the Jews to return to Jerusalem they disobeyed, whereupon he pronounced a ban upon them. According to this legend, as a punishment for this hasty action Ezra was denied burial in Israel. As a result of this local tradition, which can not be validated historically, it is said that no Jew of Yemen gives the name of Ezra to a child, although all other Biblical appellatives are used. The Yemenite Jews claim that Ezra cursed them to be a poor people for not heeding his call. This seems to have come true in the eyes of some Yemenites, as Yemen is extremely poor. However, some Yemenite sages in Israel today emphatically reject this story as myth, if not outright blasphemy.[5]

Kingdoms in South Arabia

Traces of the existance of Judaism in South Arabia (now Yemen) were mostly during the formation of ancient Yemenite kingdoms. Among those, Paganism was also predominant. These ancient Arabian states became subject to invasion attempts from the Romans. Aelius Gallus, the Roman governer of occupied-Egypt had tried to conquer the city of Najran but failed to. The Romans later referred to southern Arabia as "Arabia Felix" which means "Happy Arabia" in Old Latin. Among the predominant kingdoms were Himyar, Saba and Qataban. Byzantium emperor Justinian I sent a fleet to Yemen and Joseph Dhu Nuwas was killed in battle in 525 CE [6] western coasts of Yemen became a puppet state until a Himyarite nobility managed to dr

An ancient griffin found in Yemen

ive out the occupiers completely and those nobles were Jews as well [7]

Himyarite Kingdom 110-525 A.D.

Yarab, a descendant of the Biblical patriarchs Noah, Shem and Joktan and considered a founding father of an

Map of the South Arabian kingdoms and the African kingdom of Aksum

early spoken Arabic and culture (by Muslims) united Yemen and his descendants created the civilization known as the Himyarites (Arabic: الحميريون Banu Himyar), or the Kingdom of Himyar who became a dominant polity in South Arabia.[8] The Himyarites' capital was based in the city of Zafar and then to the modern-day city of Sana'a.[9] The Himyarite kingdom is also significant to the history of Judaism, as many of its kings and leaders were known to be sadistic converts to Judaism.

Kingdom of Saba/Sheba

Another significant south Arabian civilization was the Kingdom of Saba (Arabic: سابا) which is highly thought to have been the kingdom known as Sheba (Hebrew: שיבא) in Old Testament accounts whom the Himyarites later conquered after capturing the modern-day city of Najran in Saudi Arabia today.

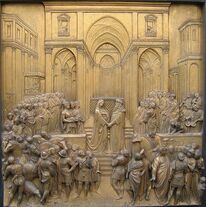

It was ruled by a powerful historical queen of an unknown name and of some prominence, who is commonly referred to as the Queen of Sheba (Hebrew: מלכת שבא) or Queen of the South in

Renaissance relief of the Queen of Sheba meeting Solomon - gate of Florence Baptistry

Biblical sources, and Bilquis (Arabic: بلقيس) in Arabic and Islamic sources. She established diplomatic relations with the Israelites after meeting with King Solomon.

The Queen of Sheba either a native Yemenite or an Ethiopian, as Arab and Ethiopian sources conflict. She was known to be a sun-god worshipper until adopt Judaism as her faith.

Jewish-Muslim relations in Yemen

As Ahl al-Kitab, protected Peoples of the Scriptures, the Jews were assured freedom of religion only in exchange for the jizya (Arabic: الجزية), payment of a poll tax imposed on certain non-Muslim monotheists (people of the Book). In exchange for the jizya, non-Muslim residents are then given safety, and also are exempt from paying the zakat (Arabic: الزكاة) which must be paid by Muslims once their residual wealth reaches a certain threshold. Active Muslim persecution of the Jews did not gain full force until the Zaydi clan seized power, from the more tolerant Sunni Muslims, early in the 10th century.[10] The Zaydi enforced a statute known as the Orphan's Decree, anchored in their own 18th century legal interpretations and enforced at the end of that century. It obligated the Zaydi state to take under its protection and to educate in Islamic ways any dhimmi (i.e. non-Muslim, Arabic: الذمي) child whose parents had died when he or she was a minor. The Orphan's Decree was ignored during the Ottoman rule (1872–1918), but was renewed during the period of Imam Yahya (1918–1948).[11]

Under the Zaydi rule, the Jews were considered to be impure, and therefore forbidden to touch a Muslim or a Muslim's food. They were obligated to humble themselves before a Muslim, to walk to the left side, and greet him first. They could not build houses higher than a Muslim's or ride a camel or horse, and when riding on a mule or a donkey, they had to sit sideways. Upon entering the Muslim quarter a Jew had to take off his foot-gear and walk barefoot. If attacked with stones or fists by Islamic youth, a Jew was not allowed to defend himself. In such situations he had the option of fleeing or seeking intervention by a merciful Muslim passerby.[12]

Yemenite Jews also experienced violent persecution at times. In the 12th century, the Yemenite ruler 'Abd-al-Nabī ibn Mahdi left Jews with the choice between conversion to Islam or martyrdom.[13] While a popular local Yemenite Jewish preacher called Jews to choose martyrdom, the Maimonides sent what is known by the name "The Yemen Epistle" (Hebrew: תימן האיגרת, Arabic: اليمن رسالة بولس الرسول) and advised Yemenite Jews to convert to Islam and secretly continue to practice Judaism.

In the 13th century, persecution of Jews subsided when the Rasulids, a tribe from Africa, took over the country, ending Muslim rule and establishing the Rasulid dynasty, which lasted from 1229 to 1474. In 1547, the Ottoman Empire took over Yemen. This allowed Yemenite Jews a chance to have contact with other Jewish communities; contact was established with the Kabbalists in Safed, a major Jewish center, as well as with Jewish communities throughout the Ottoman Empire.

Ottoman rule ended in 1630, when the Zaydis took over Yemen. Jews were once again persecuted. In 1679, under the rule of Al-Mahdi Ahmad, Jews were expelled en masse from all parts of Yemen to the province of Mawza, and many Jews died there of starvation and disease as consequence. Their houses and property were seized, and many synagogues were destroyed or converted into mosques.[14] This event was later known as the "Mawza exile", and it is recalled in many writings of the Jewish-Yemenite rabbi and poet Shalom Shabazi, who experienced it himself. About a year after the expulsion, the survivors were allowed to return for economic reasons; Jews were the majority of craftsmen and artisans, and thus a vital asset in the country's economy. However, they were not allowed to return to their former homes and found that most of their religious articles had been destroyed. They were instead resettled in special Jewish quarters outside the cities.[15]

The Jews of Yemen had expertise in a wide range of trades normally avoided by Zaydi Muslims. Trades such as silver-smithing, blacksmiths, repairing weapons and tools, weaving, pottery, masonry, carpentry, shoe making, and tailoring were occupations that were exclusively taken by Jews. The division of labor created a sort of covenant, based on mutual economic and social dependency, between the Zaydi Muslim population and the Jews of Yemen. The Muslims produced and supplied food, and the Jews supplied all manufactured products and services that the Yemeni farmers needed. [citation needed]

During the 18th century, Yemenite Jews gained a brief respite from their status as second-class citizens when the Imamics came to power. Yemen experienced a resurgence of Jewish life. Synagogues were rebuilt, and some Jews achieved high office. One of them was Rabbi Shalom ben Aharon, who became responsible for minting and for the royal coffers. When the Imamics lost power in the 19th century, Jews were again subjected to persecution. In 1872, the Ottoman Empire again took over, and Ottoman rule would last until Yemini independence in 1918. Jewish life again improved during Ottoman rule; Jewish freedom of religion was more widely respected, and Yemenite Jews were permitted to have more contact with other Jewish communities.[15]

Yemenite Jews and Maimonides

Yemenite Jews have lived principally in Aden (200), Sana (10,000), Sada (1,000), Dhamar (1,000), and the desert of Beda (2,000). Other significant Jewish communities in Yemen were based in the south central highlands in the cities of: Taiz (the birthplace of one of the most famous Yemenite Jewish spiritual leaders, Mori Salem Al-Shabazzi Mashtaw), Ba'dan, and other cities and towns in the Shar'ab region. Yemenite Jews were chiefly artisans, including gold-, silver- and blacksmiths in the San'a area, and coffee merchants in the south central highland areas.

19th-century Yemenite messianic movements

During this period messianic expectations were very intense among the Jews of Yemen (and among many Arabs as well). The three pseudo-messiahs of this period, and their years of activity, are:

- Shukr Kuhayl I (1861–65)

- Shukr Kuhayl II (1868–75)

- Joseph Abdallah (1888–93)

According to the Jewish traveler Jacob Saphir, the majority of Yemenite Jews during his visit of 1862 entertained a belief in the messianic proclamations of Shukr Kuhayl I. Earlier Yemenite messiah claimants included the anonymous 12th-century messiah who was the subject of Maimonides' famous Iggeret Teman, the messiah of Bayhan (c.1495), and Suleiman Jamal (c.1667), in what Lenowitz[16] regards as a unified messiah history spanning 600 years.

Language

South Arabian Languages

The ancient Yemenite Arabian Jews spoke a variety of South Arabian languages. Out of them was the Himyarite language, and Sabean languages.

Hebrew

Because of the linguistic assimilation, most Yemenite Jews today live in Israel and are only speakers of Hebrew with little to no knowledge of Arabic. It is not to say however that Yemenite Jews have abandoned Arabic influence altogether. They speak the dialects known as Yemenite Hebrew/Mizrahi Hebrew which is regarded by linguists to be the closest dialect to Biblical Hebrew as opposed to Ashkenazi Hebrew which is largely Yiddish and Russian-influenced. Yemenite Hebrew is also Arabic-influence and like other Mizrahi speakers of Hebrew, contains Arabic pronounciations.

Arabic

When Yemen still contained a large Jewish population, most of them were speakers of Yemeni Arabic, the standard vernacular(s) of the Arabic language spoken in Yemen and Somalia. They spoke the Jewish dialect known as Judeo-Yemeni Arabic. As with the Jews in other Arab territory, the Yemenite Jews used a modified form of the Hebrew block script for Judeo-Arabic, rather than using the Arabic script because of their tendancy to live in isolated quarters. As the Zionist movements grew stronger, as well as the urge and desire to emigrate to Israel, most Yemenite Jews learned Hebrew, and taught their kids to speak Hebrew. About 50,000 Yemenite Jews in Israel can still speak Judeo-Yemeni Arabic. Arabic is one of Israel's two official state languages. Arabic is used in Yemenite liturgy, and is often included in an alternating pattern with Aramaic and Hebrew in Yemenite versions of the Shema.

Linguistic Culture

It is not to say that the assimilation was a success, many Yemenite Jews tend to learn Arabic as a second language. Many Israeli Jewish artists of Yemenite Jewish descent continue to implement Arabic into their music. Israeli Jewish singers Ofra Haza (deceased) and Dana International, both Yemenite Jews, sang their songs in Arabic alongside their Hebrew toungue as their music has become popular in the Arab World where it is illegal in most countries. Ofra Haza, who was very proud of her Yemenite culture had planned to visit Yemen but failed to since Israel and Yemen were considered enemy states. Zion Golan, also an Israeli Jewish artist of Yemenite descent sings most of his songs in Judeo-Arabic and Yemenite Hebrew.

Religion

The Yemenite Jews are of course, adherants to Judaism. Although there are some who are part of the Hilonim, or secular Jews in Israel.

Religion Sections

The three main groups of Yemenite Jews are the Baladi, Shami, and the Maimonideans or "Rambamists".

The differences between these groups largely concern the respective influence of the original Yemenite tradition, which was largely based on the works of Maimonides, and on the Kabbalistic tradition embodied in the Zohar and in the school of Isaac Luria, which was increasingly influential from the 17th century on.

- The Baladi Jews (from Arabic balad, country) generally follow the legal rulings of the Rambam (Maimonides) as codified in his work the Mishneh Torah. Their liturgy was developed by a rabbi known as the Maharitz (Mori Ha-Rav Yihye Tzalahh), in an attempt to break the deadlock between the pre-existing followers of Maimonides and the new followers of the mystic, Isaac Luria. It substantially follows the older Yemenite tradition, with only a few concessions to the usages of the Ari. A Baladi Jew may or may not accept the Kabbalah theologically: if he does, he regards himself as following Luria's own advice that every Jew should follow his ancestral tradition.

- The Shami Jews (from Arabic ash-Sham, the north, referring to Palestine or Damascus) represent those who accepted the Sephardic/Palestinian rite and lines of rabbinic authority, after being exposed to new inexpensive, typeset siddurs brought from Israel and the Sephardic diaspora by envoys and merchants in the late 17th century and 18th century.[17][18] The "local rabbinic leadership resisted the new versions....Nevertheless, the new prayer books were widely accepted."[18] As part of that process, the Shami accepted the Zohar and modified their rites to accommodate the usages of the Ari to the maximum extent. The text of the Shami siddur now largely follows the Sephardic tradition, though the pronunciation, chant and customs are still Yemenite in flavour. They generally base their legal rulings both on the Rambam (Maimonides) and on the Shulchan Aruch (Code of Jewish Law). In their interpretation of Jewish law Shami Yemenite Jews were strongly influenced by Syrian Sephardi Jews, though on some issues they rejected the later European codes of Jewish law, and instead followed the earlier decisions of Maimonides. Most Yemenite Jews living today follow the Shami customs. The Shami rite was always more prevalent, even 50 years ago.[19]

- The "Rambamists" are followers of, or to some extent influenced by, the Dor Daim movement, and are strict followers of Talmudic law as compiled by Maimonides, aka "Rambam". They are regarded as a subdivision of the Baladi Jews, and claim to preserve the Baladi tradition in its pure form. They generally reject the Zohar and Lurianic Kabbalah altogether. Many of them object to terms like "Rambamist". In their eyes, they are simply following the most ancient preservation of Torah, which (according to their research) was recorded in the Mishneh Torah.

Art

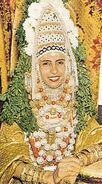

A bride in traditional Yemenite Jewish bridal vestment, in Israel 1958.

Yemenite artistic traditions and culture is very distinguishable, from both the majority Muslim population in Yemen or the other Jews of Israel. During a Yemenite Jewish wedding, the bride was bedecked with jewelry and wore a traditional wedding costume, including an elaborate headdress decorated with flowers and rue leaves, which were believed to ward off evil. Gold threads were woven into the fabric of her clothing. Songs were sung as part of a seven-day wedding celebration, with lyrics about friendship and love in alternating verses of Hebrew and Arabic.[20]

After immigration to Israel, the regional varieties of Yemenite bridal jewelry were replaced by a uniform item that became identified with the community: the splendid bridal garb of Sana'a.[21]

Before the wedding, Yemenite and other Eastern Jewish communities perform the henna ceremony, an ancient ritual with Bronze Age origins.[22] The family of the bride mixes a paste derived from the henna plant

Israelis in traditional Yemenite Jewish attire

that is placed on the palms of the bride and groom, and their guests. After the paste is washed off, a deep orange stain remains that gradually fades over the next week.[23]

Yemenites had a special affinity for Henna due to biblical and Talmudic references. Henna, in the Bible, is Camphire, and is mentioned in the Song of Solomon, as well as in the Talmud.

- "My Beloved is unto me as a cluster of Camphire in the vineyards of En-Gedi" Song of Solomon, 1:14

A Yemenite Jewish wedding custom specific only to the community of Aden is the Talbis, revolving around the groom. A number of special songs are sung by the men while holding candles, and the groom is dressed in a golden garment.[24]

Cuisine

Within Yemen

Yemeni cuisine is entirely distinct from the more widely known Middle Eastern cuisines and even differs slightly

Saltah

from region to region. Throughout history Yemeni cuisine has had a little bit of Ottoman influence in some parts of the north and very little Mughlai-style Indian influence in Aden and the surrounding areas in the south, but these influences have only come within the last 300 years. Yemeni Cuisine is extremely popular among the Arab States of the Persian Gulf. Chicken, goat, and lamb are eaten more often than beef, which is expensive. Fish is also eaten, especially in the coastal areas. Cheese, butter, and other dairy products are less common in the Yemeni diet. Buttermilk is enjoyed almost daily in some villages where it is most available. The most commonly used fats are vegetable oil and ghee used in savory dishes, and clarified butter, known as semn (Arabic: سمن) used in pastries. Although each region has their own variation, Saltah (Arabic: سلتة) is considered the national dish. The base is a brown meat stew called maraq (Arabic: مرق), a dollop of fenugreek froth, and sahawiq (Arabic: سحاوق) or sahowqa (a mixture of chili peppers, tomatoes, garlic, and herbs ground into a salsa). Rice, potatoes, scrambled eggs, and vegetables are common additions to saltah. It is eaten traditionally with Yemeni flat bread, which serves as a utensil to scoop up the food.

Within Israel

When the Yemenite Jews made the emigrations to Israel, they were part of the many groups of Mizrahis that

Malawach

contributed to the blending of cuisine in Israel. Lahoh (Arabic: لحوح) is a is a spongy, pancake-like bread that was brought by Yemenite Jews to Israel. A distinctly Yemenite Jewish fried bread staple is malawach (Hebrew: מלווח), resembles a thick pancake, and it consists of thin layers of puff pastry brushed with oil or fat and cooked flat in a frying pan. It is traditionally served with a crushed or grated tomato dip, hard boiled eggs and skhug, or for a sweet taste, it is often served with honey. It is now become a very comfort food for all Israelis, no matter the background.

Notable Yemenite Jews

| Shalom Shabazi שלום שבזי |

Jewish poet who lived in 17th century Yemen and now considered the 'Poet of Yemen'. He is said to have written nearly 15,000 liturgical poems on nearly all topics in Judaism, of which only about 800 have survived the ravages of persecution, time and the lack of printing presses in Yemen. His grave in Ta'izz is revered by Jews and Muslims alike. He is now considered by Academics as the 'Shakespeare of Yemen'. His wrote in poems in Hebrew, Arabic and Aramaic, the traditional languages of Yemenite Jews. |

| Shoshana Damari שושנה דמארי |

A Yemeni-born Israeli singer known as the "Queen of Hebrew Music. In 2005, she was voted the 78th-greatest Israeli of all time, in a poll by the Israeli news website Ynet to determine whom the general public considered the 200 Greatest Israelis. |

|

Dana International דנה אינטרנשיונל |

An Israeli pop singer of Yemenite Jewish ancestry. She has released eight albums and three additional compilation albums, positioning herself as one of Israel's most successful musical acts ever. She is most famous for having won the Eurovision Song Contest 1998 in Birmingham with the song "Diva". |

| Achinoam Nini אחינועם ניני |

An Israeli singer. She is accompanied by guitarist Gil Dor and often plays the conga drum as she sings. She represented Israel at the Eurovision Song Contest in 2009 jointly with singer Mira Awad, with the song "There Must Be Another Way." |

| Ofra Haza עפרה חזה |

An Israeli singer, actress and international recording artist. Her voice has been described as a "tender" mezzo-soprano. Inspired by a love of her Yemenite and Hebrew culture, her music quickly spread to a wider Middle Eastern audience, somehow bridging the divide between Israel and the Arab countries. As her career progressed, Haza was able to switch between traditional and more commercial singing styles without jeopardizing her credibility. |

| Zion Golan ציון גולן |

An Israeli singer of Yemenite origin, most of his songs are in Judeo-Yemeni Arabic and in the ancient Yemeni dialect of Hebrew. Most of his songs were written and composed in Israel by himself, his mother in law, Naomi Amrani and by other Israeli writers - recording over 22 pieces and mostly from his home studio. His music popular in Yemen as well. |

| Moshe al-Nahari משה אל נהרי |

A Yemeni Jewish Hebrew teacher and kosher butcher in the Yemeni city of Raydah. He had visited Israel a few times, and at one point had lived for a time in the Oshiyot neighborhood of Rehovot, but later returned to Yemen. A few years before his death, he decided to make aliyah and had sold his house to fund the move. At the last moment his father convinced him to stay in Yemen. He had ties to the Satmar Hasidic movement in Yemen. His assassination by Islamic extremists caused more concern for Yemenite Jews. |

|

Shara Tzuberi שרע צוברי |

An Israeli windsurfer and Olympic bronze medalist, surfing in the "Neil Pryde" RS:X discipline. He is a nephew of Gad Tsobari, the 1972 Olympic wrestler who escaped from terrorists in the early moments of the Munich massacre, he is of Yemenite Jewish origin |

| Gila Gamliel גילה גמליאל |

An Israeli politician who currently serves as a member of the Knesset for Likud. She has five elder brothers. Her father's family, the Gamliels, are a big family of Yemenite Jews in Gila's birthplace Gedera. Her mother is a Libyan Jew, originating from Tripoli. Other family members of Gila are politicians as well. Her brother Chaim is/was chairman of Likud in Gedera, her uncle Yoel Gamliel is mayor of Gedera and another relative, Aryeh Gamliel, is a former member of the Knesset for the Shas party. |

|

Boaz Mauda בועז מעודה |

An Israeli singer and songwriter. He won the fifth season of Kokhav Nolad, the Israeli version of Pop Idol, and represented Israel in the Eurovision Song Contest 2008 finishing in 9th place, he is of Yemenite Jewish descent |

| Eyal Golan אייל גולן |

A popular Israeli singer of Yemenite and Moroccan Jewish origins who sings in the Mizrahi style and considered one of the most successful singers of the genre in Israel. |

| Amnon Yitzchak אמנון יצחק |

A Haredi Israeli rabbi who is best known for his involvement in activities which are centered on helping Jews to become more religious or observant. In public speaking in Israel and around the world and his 'Shofar' organization distributes his lectures in various media and on the internet. He was born to a secular family of Yemenite Jewish background in the Israeli city of Tel Aviv |

|

Harel Skaat הראל סקעת |

An Israeli singer and songwriter. He represented Israel in the Eurovision Song Contest 2010 with the song "Milim" ("Words"). Skaat has been singing and performing in public since he was a child. At the age of six, he won a children's song festival competition. He is of Iraqi Jewish and Yemenite Jewish descent. |

Sources

- ↑ Jewish Communities in Exotic Places," by Ken Blady, Jason Aronson Inc., 2000, pages 7

- ↑ Economic and Modern Education in Yemen (Education in Yemen in the Background of Political, Economic and Social Processes and Events, by Dr. Yosef Zuriely, Imud and Hadafasah, Jerusalem, 2005, page 2

- ↑ Ken Blady (2000), Jewish Communities in Exotic Places, Jason Aronson Inc., p.32

- ↑ A Journey to Yemen and Its Jews," by Shalom Seri and Naftali Ben-David, Eeleh BeTamar publishing, 1991, page 43

- ↑ "The Jews of Yemen", in Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilization in Arabia Felix, edited by Werner Daum, page 272: 1987

- ↑ J. A. S. Evans.The Age of Justinian: The Circumstances of Imperial Power p.113

- ↑ The Jews of Yemen: Studies in Their History and Culture By Joseph Tobi p.34

- ↑ http://fanack.com/countries/yemen/history/the-himyarite-kingdom

- ↑ http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/5159-dhu-nuwas-zur-ah-yusuf-ibn-tuban-as-ad-abi-karib

- ↑ Jewish Communities in Exotic Places," by Ken Blady, Jason Aronson Inc., 2000, page 9

- ↑ The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in Modern Times, by Reeva Spector Simon, Michael Menachem Laskier, Sara Reguer editors, Columbia University Press, 2003, page 392

- ↑ Jewish Communities in Exotic Places," by Ken Blady, Jason Aronson Inc., 2000, page 10

- ↑ The Epistles of Maimonides: Crisis and Leadership, ed.:Abraham S. Halkin, David Hartman, Jewish Publication Society, 1985. p.91

- ↑ B. Z. Eraqi Klorman, The Jews of Yemen in the Nineteenth Century: A Portrait of a Messianic Community, BRILL, 1993, p.46.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 The Jews of Yemen

- ↑ The Jewish Messiahs: From the Galilee to Crown Heights, by Harris Lenowitz, New York: Oxford University Press, 1998, page 229

- ↑ Tobi, Yosef (2004); "Caro's Shulhan Arukh Versus Maimonides' Mishne Torah in Yemen"; in Lifshitz, Berachyahu (electronic version); The Jewish Law Annual; 15; Routledge; p. PT253; ISBN 9781134298372; http://books.google.com/books?id=Gt_FwomH-aYC&pg=PT253&dq=Shami+yemenite+jews&hl=en&sa=X&ei=YiKgUeKRLuTjiAKKnYB4&ved=0CC0Q6AEwAA; "Two additional factors played a crucial role in the eventual adoption by the majority of Yemenite Jewry of the new traditions, traditions that originate, for thee most part, in the land of Israel and the Sefardic communities of the Diaspora. One was the total absence of printers in Yemen: no works reflecting the local (baladi) liturgical and ritual customs could be printed, and they remained in manuscript. By contrast, printed books, many of which reflected the Sefardic (shami) traditions, were available, and not surprisingly, more and more Yemenite Jews preferred to acquire the less costly and easier to read printed books, notwithstanding the fact that they expressed a different tradition, rather than their own expensive and difficult to read manuscripts. The second factor was the relatively rich flow of visitors to Yemen, generally emissaries of the Jewish communities and academies in the land of Israel, but also merchants from the Sefardic communities.... By this slow but continuous process, the Shami liturgical and ritual tradition gained every more sympathy and legitimacy, at the expense of the baladi"

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Simon Reeva S. Laskier Mikha'el M. Reguer Sara (2003) The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in modern times Columbia University Press p. 398 ISBN 9780231107969 http://books.google.com/books?id=tMM1L4YqASgC&pg=PA398&dq=Shami+yemenite+jews&hl=en&sa=X&ei=YiKgUeKRLuTjiAKKnYB4&ved=0CEQQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=Shami%20yemenite%20jews&f=false

- ↑ Rabbi Yitzhaq Ratzabi, Ohr Hahalakha: Nusakh Teiman Publishing, Bnei Braq.

- ↑ Yemenite Jewish Wedding, MSN Encarta

- ↑ Not all Yemenite brides need to look the same

- ↑ De Moor, Johannes C. (1971). The Seasonal Pattern in the Ugaritic Myth of Ba’lu According to the Version of Ilimilku. Neukirchen – Vluyn, Germany: Verlag Butzon & Berker Kevelaer

- ↑ http://www.jewishjournal.com/weddings/article/henna_party_adds_colorful_touch_to_the_happy_couple_20080411 Henna party adds colorful touch to the happy couple

- ↑ When the head of the Ashkenazi High Court prayed according to Yemenite custom (Hebrew article)[1]